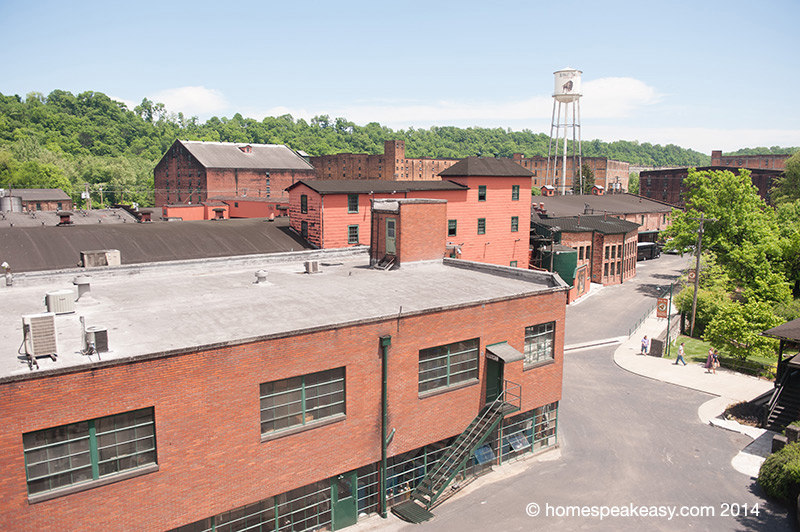

The third stop on the trip was to Buffalo Trace, producer of several of my favorite bourbons. We called in advance and were set up with a pretty great private tour of the inner workings of the distillery. It happened to be a Sunday and no one was actually working, which turned out to be fortunate for us in terms of what we could see.

Buffalo Trace has been operating continuously since 1786, Originally opened by Colonel E. H. Taylor as O.F.C. Distillery (Old Fire Copper) and the Carlysle Distillery. George T. Stagg lent Taylor money, and eventually foreclosed on the distillery for non-payment. Taylor opened a second distillery down the road, which was eventually bought out by Beam, Inc., the name of E. H. Taylor along with it. Later, Buffalo Trace was bought out by Sazerac, and in 1992 they traded a vodka brand to Beam to recover the license to use the name E. H. Taylor, the original founder of their distillery.

Through the whole story, I was most surprised to find that George T. Stagg, a big name in whiskey, was never a distiller himself, but a money lender that ended up with a distillery of his own through foreclosure.

Buffalo Trace weathered prohibition by producing medicinal alcohol. 6 million prescriptions for 100-proof whiskey were filled at the distillery in a state with a population of 1.4 million at the time. The prescription allowed for 1 pint of whiskey every 10 days, but were often written for every member of the family, so a fan of the drink could bring his 6 children and wife, and leave with 8 pints to carry him through the next week and a half. The prescriptions were handed out for just about anything that was difficult to define concretely, like the weed card of its day. During this time, George Dickel also ducked shutdown during prohibition by relocating its distillery to the Buffalo Trace property.

First stop along the path to whiskey is the weigh station for the grain deliveries, which arrive 5-7 times every day. The corn is checked regularly to ensure quality and lack of GMO product, then the grain is sent up to the grinding mill, dumped into the hoppers, and finally dumped into the cookers. The grains are cooked individually, and then mixed together for the mash. Following the first stage of the distilling process, the spent grain is then piped into large roasters to remove the moisture and condense it into a feed that tastes surprisingly like Grape Nuts. To prevent wasted trips, the trucks delivering the grain are then filled with the roasted spent grain, and sent back to the farm to be used as feed.

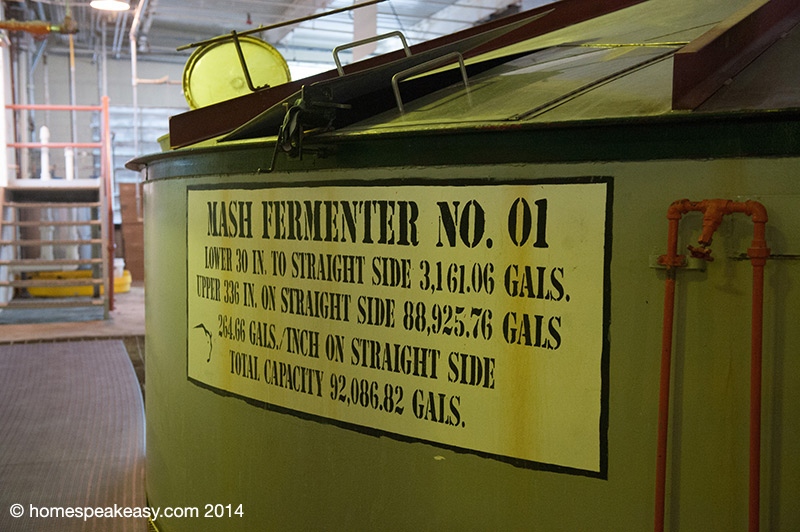

Buffalo Trace only produces 3 mashbills for all its products: 2 corn and one rye. The mash is then combined with the yeast, a single strain that has been propagated for 129 years, and is maintained on 6 continents to ensure its safety in the event of disaster. Just like everyone else, they ferment the mash and pipe it to the still with some of the last batch to be distilled into whiskey. The process of adding the previous batch to the current is called “Sour Mash,” and is used to ensure continuity of flavor.

The most interesting part of the Buffalo Trace distillery (for me, at least) is that there is a microdistillery right in the middle of everything. One self-contained room with cookers, fermenters, and a little 250 gallon pot still that Buffalo Trace’s master distiller uses to experiment on his quest to find the “perfect” whiskey. It’s here that the Buffalo Trace Experimental Collection and Single Oak Projects are made, and any future bottlings that haven’t yet come to be.

Finally, the ricks. Interestingly, Buffalo Trace’s 13 rickhouses are brick buildings, unlike the wood-and-tin structures at Heaven Hill and Willett. They currently have 400,000 barrels on the property, and like Willett, they do not rotate. All the Blanton’s Bourbon comes from the Blanton rickhouse and the high-rye mashbill #2, etc. The incredibly specific tradition of it all is endlessly interesting to me.

At the end of the tour, our guide clarified the one hazy portion of the definition of “bourbon” for us. We’d been hearing it had to be matured for 2 years, 4 years, and “as long as it passes through a charred barrel.” It turns out, it’s all 3. Bourbon whiskey only needs to pass through a charred white american oak barrel. “Straight” bourbon whiskey must spend a minimum of 2 years maturing in the barrel, but must list the number of months it spent there right up until 4 years. So basically: “Bourbon Whiskey” could be any age at all. If the label reads “Straight Bourbon Whiskey,” and has no age listed, you know it is at least 4 years old.

I can’t recommend the “hard hat” tour enough, we got to see a great deal of the distillery that we might not have known about otherwise. And if you happen to get David for a tour guide, you’re in for a treat. The guy knows his stuff.

Next up: Four Roses

Here are the Federal Regs if you ever need them

http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=64fd0525ea00c207dbc6c2247244df27&node=sp27.1.5.c&rgn=div6